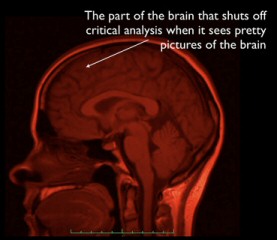

Go to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) website right now and you’ll see brains. Pictures, graphics, scans — a colorful display. You’ll also see a photo of Nora Volkow, NIDA’s director, whose “work has been instrumental in demonstrating that drug addiction is a disease of the human brain.” This would be all well and good, if pictures (or any other representation or analysis) of what’s going on in a drug user’s brain actually demonstrated that addiction is a brain disease. But they don’t. How it is that “we have come to believe” this irrational notion, that it has become the accepted truth among both lay people and professional orthodoxy, is simply mind-boggling to me.

As Stanton Peele has pointed out again and again, including today on his Psychology Today blog, the brain disease model of addiction defies both common sense and a reasonable interpretation of scientific research:

The chronic brain disease model doesn’t explain the most fundamental things about addiction, like how the vast majority of people overcome it without treatment, that there are no measurable biological means to determine whether and when people are addicted and when they are not, nor is there any treatment that addresses the supposed dopamine-based nature of addiction. In fact, the best science and therapy both point towards an entirely opposite, real-world way of defining “recovery.”

Meanwhile, as the idea of addiction as a brain disease is imbedded in our culture, we simply get more and more examples of brain diseases as more and more things are understood as addictions, and as we spread the idea further and thinner than any possibly scientific explanation can be spread.

This idea is not an expression of science. It is, instead, a cultural myth, one that the best and the brightest are obligated to endorse to be recognized as mainstream thinkers.

Don’t get me wrong — I’m all for learning as much as possible about the physiological and neurological aspects of addiction, and of all other realms of human experience for that matter. Of course brains (our organism/physiology in general) are absolutely foundational to all that we experience. A baseball bat to the head is all the evidence needed to establish that fact. But how, pray tell, does the plainly evident and obvious fact that all human experience is grounded and reflected in wonderfully complex and interesting ways in the brain and body lead to the notion that so many of our life problems are therefore fundamentally diseases of the brain? Imagine Nora Volkow’s perfect scenario, that after years of research we have finally and perfectly mapped all the changes that happen in the brain over the complete course of drug use and addiction. Imagine that brain scan technology could yield perfect scans and that we understood and interpreted the images perfectly. To my mind that still wouldn’t lend a shred of evidence to the notion that addiction is a brain disease.

A quick thought experiment: You are hooked up to this hypothetical machine (a super scanner) which can perfectly record all changes in your body’s and brain’s physiology, demonstrating with perfect accuracy every deviation from healthy homeostasis. You are put in room. In through the door on the far end walks a tiger. Your body and brain begin to go haywire. Hormones and neurotransmitters are sloshing around and completely transform your state of existence from one of total health and relaxation to one of total stress. The super scanner perfectly records every change and quickly prints out a recipe for a drug that will re-balance your system, with minimal side effects. While your state of stress and imbalance is clearly and dramatically grounded and reflected in your physiology, isn’t it a bit shortsighted to think of your problem solely or even primarily in those terms? If someone were to drop a cage on the tiger, your physiology would quickly and naturally move back to homeostasis without any need for a drug or any other physiological intervention. Your problem was primarily the presence of the tiger, not the changes in your brain that the presence of the tiger inspired. The solution–i.e. the appropriate intervention–to the problem was primarily social and behavioral, not physiological. In fact, the information provided by the super scanner, interesting as it might be, was completely irrelevant in terms of the practical solution to the problem.

Drug use and abuse changes what’s going on in the brain. Yes. Everything we do and everything that happens to us changes what goes on in the brain. Yes. Therefore, deviations from healthy, homeostatic brain and body states are best thought of as diseases of the brain? Not so fast Dr. Volkow. Studying objective brain changes is one of many perspectives that are worthy of consideration, focus, and scrutiny. Taken together with subjective, relational, behavioral, social, and cultural perspectives, we might yet arrive at a truly comprehensive, rational, integral approach to helping those seeking health and well-being.