Sometimes when I listen to the old recordings Alan Watts left behind, I imagine them as a present-day podcast, and I think, “This is better, more interesting, and more relevant than 99.9% of anything I’m listening to in 2021.” Here he reflects on the nature of truth, in 1959.

Legitimate criticism of scientific authority in truthless times

More and more it seems to me that we are living in a world where a critical mass of people lack the necessary critical thinking skills to engage in reasonable discussions about the most important issues of our time. This is a big problem. There is a long lost territory known as “reasonable disagreement” that used to be a starting place for dialogue and engagement and understanding the various perspectives that intelligent, sensitive humans can hold. But in order to get to that hallowed, fertile ground of reasonable disagreement, we must presuppose reason, for we can’t hope to transcend the limits of the tool without using it to its full potential first.

More and more it seems to me that we are living in a world where a critical mass of people lack the necessary critical thinking skills to engage in reasonable discussions about the most important issues of our time. This is a big problem. There is a long lost territory known as “reasonable disagreement” that used to be a starting place for dialogue and engagement and understanding the various perspectives that intelligent, sensitive humans can hold. But in order to get to that hallowed, fertile ground of reasonable disagreement, we must presuppose reason, for we can’t hope to transcend the limits of the tool without using it to its full potential first.

I have lamented–ad nauseum, perhaps–about how little we seem to value critical thinking in these strange, strange times, and have argued that a minimum level of development of critical thinking skills is essential for any and all of us to move forward effectively in any of our respective endeavors, including our attempts to make sense of and utilize health-related information. However, the truth is – if indeed there is such a thing as truth! – that even when one possesses the requisite skills, it’s still an extremely difficult task to evaluate the validity of people’s claims, interpretations, and recommendations, even when those people are regarded as experts in their respective fields. This is where things get especially gnarly, because anti-intellectualism would be a big enough problem were it simply a matter of the ignoramus stubbornly refusing to yield to the expert’s relatively enlightened perspective. Things get gnarly because the ignoramus might be right some of the time, albeit for the wrong reasons. After all, experts and authorities in a variety of fields (e.g., psychiatry) are so often corrupted by misaligned incentives, biases, and conflicts of interest, that we are right not to place our trust in them. At the same time, we are wrong to throw out the baby with the bathwater, and so we clearly need to find some way of reforming our information and knowledge systems/structures, rather than surrendering to the forces of obfuscation and corruption.

In a recent article (America’s Cult of Ignorance—And the Death of Expertise) by Tom Nichols, the author laments the various campaigns against “established knowledge” that, while nothing new, have reached somewhat of a fever pitch in our current information environment, where accusations of “fake news” are hurled at everything from completely fabricated nonsense on the one hand, to major news outlets like The New York Times on the other. The ascendant forces of anti-intellectualism have speciously twisted the concept of democracy into the notion that, as Isaac Asimov put it, “my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.” “Established knowledge,” however, can be shaped and distorted so much by corrupting influences that it is only through the relentless questioning of authority that dangerous bullshit gets exposed. So, how can we expose and challenge the bullshit and corruption that has corroded the information pipeline without undermining confidence in the entire project of a scientifically-informed approach to knowledge?

Back in 2005, John Ioannidis wrote a paper called Why Most Published Research Findings Are False, and apparently it has since become the most cited piece related to the topic at hand. In the paper Ioannidis laid bare many of the influences – from flawed methodology to statistical hocus-pocus to flat-out financial conflicts of interest – that had shaken his confidence in the validity of most scientific research across many academic disciplines. It was quite a gut-punch to the entire academy, delivered by one of their own, and it definitely changed the way I consume and evaluate information coming from both academic and media outlets. In my case, at least, the change was unambiguously positive. When I was in graduate school working toward a master’s degree in mental health counseling, I put forth the extra effort to check and challenge the interpretations and conclusions of my textbook authors and my instructors. Most of my peers, however, seemed quite content to passively accept as “established knowledge” any statement in a textbook that happened to have a citation after it, as if the name and date inside those parentheses was all that was needed to validate a given claim.

Since Ioannidis’s seminal paper, there have been many follow-up articles and discussions that are well worth reading, including the following:

- Lies, Damned Lies, and Medical Science, by David H. Freedman

- “Evidence-based medicine has been hijacked:” A confession from John Ioannidis, by Retraction Watch

- Evidence-based medicine has been hijacked: a report to David Sackett, by John Ioannidis

- The hijacking of evidence-based medicine, by David Gorski

After reading these articles, it’s hard not to have one’s confidence in scientific authority seriously undermined, and it’s easy to see how anti-intellectuals could seize upon and distort this “soul searching in the sciences” to further their agenda of obfuscation and false equivalencies. It should be obvious, however, that there is nothing anti-intellectual about challenging established knowledge with reason, sound argument, and the critical review of evidence.

One of the best ways I know of to recognize a sound, strong argument is when the proponent of that argument is willing to directly address counter-arguments, ideally in their “steelman” form. Steel-manning is basically the opposite of straw-manning, and so instead of caricaturing another person’s point of view in your take-down of it, you instead seek to engage with the strongest possible version of their idea, even if they didn’t present their thoughts very cogently in the first place. This show of good faith can go a long way in creating the conditions in which a productive conversation can flourish, but there are always potential landmines. The biggest difficulty I’ve encountered when engaging in “difficult discussions” is in coming to basic agreement on the validity of whatever data or research is referenced. Even with the advent of Google, one can’t be expected to fact-check information and critique complex interpretations of data in real time, during a discussion. My rule of thumb is that if one’s argument rests on research and data which is unfamiliar to your interlocutor, one is obliged to accurately summarize the details of whatever research and data is being referred to, as opposed to expecting the other person to accept a fallacious appeal to authority, as when one weakly insists that “research shows” or “it’s been proven that” such and such is the case. Unfortunately, it is rarely the case that people actually familiarize themselves first-hand with the evidence supporting their points of view, and instead they merely place their trust in some expert or voice of authority who, more often than not, is selected as a trusted information source through a process of blind confirmation bias.

Take, for example, the idea of “power posing” as an effective way to use intentional changes in body language to improve our self-confidence and performance. Let’s say that my friend Toby watches the millions-of-times-viewed TED talk by Dr. Amy Cuddy called “Your body language shapes who you are.” In that talk, Dr. Cuddy makes the case, based on scientific research, that holding one’s body in a powerful pose, like raising one’s fists in the air, can trigger physiological changes that increase one’s confidence and performance in a variety of contexts. Toby might say something to me like, “You should do a power pose before recording your podcasts. Studies show that doing so changes your biochemistry and makes you perform better.” Now, Toby himself has never read the studies in question, but he trusts that the smart-sounding and charismatic Dr. Cuddy has given him objective, sound information that can be taken to the bank. I might then say to Toby, “Not true dude. I just watched a different TED talk, by someone named Laura Arnold, where she totally debunks all of Cuddy’s research. Turns out it’s total bullshit dude.” Now, of course, I didn’t read any of the research cited by Laura Arnold in her Ted talk. I just have an affinity for debunkers, skeptics, and takedowns of authority in general. So now Toby and I seem, on the surface, to have evidence-based points of view that are colliding in a zone of reasonable disagreement, yet neither one of us has even bothered to look at the evidence in question. Rather, we have both simply argued from authority, selecting experts that have put forth points of view that appeal to each of us, respectively. Ideally, Toby and I would recognize the confirmation bias at play, and then either dig into the relevant research before reconvening, or else set the validity of the research aside and move on to explore other aspects of the issue, like our own personal experiences with body language and its effects, that don’t depend on questionable scientific evidence.

I suppose I’ve rambled on long enough about this. Below are the relevant links, and some more that I haven’t yet checked out fully. I particularly look forward to checking out the website Calling Bullshit (In the Age of Big Data). It seems like it might be just the medicine for what ails me. The authors pose the problem in such a refreshingly frank way: “The world is awash in bullshit” and “we’re sick of it.” And so their mission is “to help students navigate the bullshit-rich modern environment by identifying bullshit, seeing through it, and combating it with effective analysis and argument.”

Sounds like just what the doctor ordered. But then again, aren’t they all just shills in white coats?

Links:

- Lies, Damned Lies, and Medical Science, by David H. Freedman

- Why Most Published Research Findings Are False, by John Ioannidis

- “Evidence-based medicine has been hijacked:” A confession from John Ioannidis, by Retraction Watch

- Evidence-based medicine has been hijacked: a report to David Sackett, by John Ioannidis

- The hijacking of evidence-based medicine, by David Gorski

- Calling Bullshit (In the Age of Big Data), by Carl T. Bergstrom and Jevin West

- Psychology’s Meta-Analysis Problem, by Hilda Bastian

- The Four Most Dangerous Words? A New Study Shows, by Laura Arnold

- How Flawed Science Is Undermining Good Medicine, by Richard Harris

The role of biology in problems of thinking, feeling, and behaving

It’s a new year, and I find myself living in a “post-fact” world of “fake news” with catastrophic failures of critical thinking everywhere on display. Happy New Year everybody! What holds true–if anything holds true these days–in the realm of politics is not fundamentally different from what holds true in other areas of discourse, like say, behavioral health. And that true thing is this: our current capacity for critical thinking cannot seem to adequately process, evaluate, and analyze the constant flow of information that is being channeled through structures designed to further agendas rather than deepen knowledge and improve understanding. That was a mouthful, I know. I just can’t help wondering though, Has all this blogging been just pissing in the wind? Have I myself been duped, or been duping myself, into a false sense of certainty and self-righteousness? Maybe. But at least I’m trying. At least I care enough to ask questions.

The first Friday of every month I attend a continuing education training for mental health professionals. The training takes place in a local psychiatric hospital, and is conducted by various local leaders in the mental health profession. This last training was on the topic of addiction treatment, and I was expecting to get a heavy dose of twelve-step and brain disease dogmatism, and that’s just what happened. What took me by surprise was how starkly unscientific the presentation was–not a single reference to a single piece of research, and how uncritical the audience was as they nodded their heads to statements like “This disease wants you dead!” I felt like I was in a church listening to a sermon. I left the training deflated and discouraged. How can there be any hope of a sane, scientifically grounded approach to drug abuse (or any mental health problem for that matter) when the thought leaders, experts, and armies of professionals are all in lock-step headed in the wrong direction? Fortunately, there are dissident voices breaking through via the internet ether waves. But again, perhaps I have constructed my own cozy echo-chamber in this regard. You be the judge.

Johann Hari, he of “Chasing the Scream” and TED notoriety, wrote an interesting op-ed in the LA Times the other day called “What’s really causing the prescription drug crisis?” The piece pokes holes in the most well-subscribed narrative regarding the current opiate crisis in America, namely that Big Pharma has hooked everyone on irresistible drugs, and that what we need to do now is restrict access to these powerful life-ruining substances. The holes in this theory might not seem obvious. Even John Oliver, whose entertaining critiques usually strike the right tone, seems to have blown past them.

First of all, Hari points out that less than one percent of opiate prescriptions lead to addiction, and that super strong opiates (like diamorphine) are routinely administered in hospital settings in other countries without causing people to become addicted. So, then, the drugs themselves can’t be root of the problem, right? If it were the drugs themselves, then opiate addiction should be spread evenly across the country to match prescription rates. But it isn’t. Opiate addiction is concentrated in areas where times are the toughest, like in the Rust Belt. It’s the tough times–and their impact on people who may lack the resources (internal and external) to cope with them–that are more likely to be the root of the problem, rather than any specific numbing agent. Furthermore, how can stringent opiate restriction be the best response to the problem, when the vast majority of people who use the drugs to manage pain don’t show problematic use, and when cutting addicted folks off from their prescriptions so clearly leads them to black market heroin use? This “War on Drugs” mentality might be well-intentioned, but it’s just making things worse. In order to come up with a more effective solution, we need to fully understand the problem, which means taking into account all of the facts, which would lead us toward addressing root causes (like poverty, social isolation, poor coping skills) instead of restricting the latest, most available, most potent means of killing the associated pain.

Of course, addiction is just one category of so-called “mental illness,” and a broader argument can (and has) been made against viewing problems of thinking, feeling, and behaving, in general, as biologically driven processes best suited for physiologically focused interventions. I have been pissing in that wind for years as well, but I have not come across a more thorough critique of the predominant psychiatric paradigm than in this recent article by Phil Hickey called The Biological Evidence for “Mental Illness.” Hickey makes many of the points that I have made–ad nauseam–in previous posts (e.g., HERE), but he makes them far more meticulously and convincingly. He also grounds his arguments in research and years of clinical experience. Here are a few of Hickey’s ideas from this article that are well worth chewing on:

Depression, either mild or severe, transient or lasting, is not a pathological condition. It is the natural, appropriate, and adaptive response when a feeling-capable organism confronts an adverse event or circumstance. And the only sensible and effective way to ameliorate depression is to deal appropriately and constructively with the depressing situation. Misguided tampering with the person’s feeling apparatus is analogous to deliberately damaging a person’s hearing because he is upset by the noise pollution in his neighborhood, or damaging his eyesight because of complaints about litter in the street.

What psychiatry calls mental illnesses are actually nothing more than loose collections of vaguely-defined problems of thinking, feeling, and/or behaving. In most cases the “diagnosis” is polythetic (five out of nine, four out of six, etc.), so the labels aren’t coherent entities of any sort, let alone illnesses. But the problems set out in the so-called symptom lists are real problems. That’s not the issue. I refer to these labels as inventions, because of psychiatry’s assertion that the loose clusters of problems are real diseases. In reality, they are not genuine diseases; they are inventions. They are not discovered in nature, but rather are voted into existence by APA committees.

Both Hari and Hickey hit the nail on the head by pointing out what should be obvious, namely that addiction and other psychological problems are most often matters of adaptation, of learning, which are process that all healthy, normal brains participate in as they interact with their respective environments. How else could it be that the vast majority of people with such problems get better through such means as talking things out, rearranging their priorities, determination to change habits, and improving relationships? While it’s true–again, obviously–that every subjective human experience is grounded in some activity happening in the brain from moment to moment, it is sheer nonsense to assume that common problems faced by vast numbers of human beings are matters of hardware malfunction. This might be true for the very few. But it is only through misaligned incentives and misapplied critical thinking that the brain disease paradigm has become mental health dogma.

*Mic drop*

Brant Cortright on the role of neurogenesis in holistic health

I took a counseling class (Transpersonal Psychotherapy) with Dr. Brant Cortright while I was working on my first master’s degree at the California Institute of Integral Studies, way back in 1995. I liked him a lot. He had a gentle, genuine vibe about him. I can’t remember how it came to be that Dr. Cortright reappeared on my radar, but somehow I got wind that his recent work has to do with “neurogenesis” and its importance to holistic health.

I took a counseling class (Transpersonal Psychotherapy) with Dr. Brant Cortright while I was working on my first master’s degree at the California Institute of Integral Studies, way back in 1995. I liked him a lot. He had a gentle, genuine vibe about him. I can’t remember how it came to be that Dr. Cortright reappeared on my radar, but somehow I got wind that his recent work has to do with “neurogenesis” and its importance to holistic health.

Neurogenesis refers to the growth of new brain cells throughout life. According to Dr. Cortright, it was only recently discovered that neurogenesis happens beyond our 20s, and supposedly there is now sufficient research to support the notion that one’s rate of neurogenesis may be the most important biomarker for brain health. Furthermore, according to Cortright, a healthy brain will translate to optimal health at all levels: body, mind, heart, spirit. Low rates of neurogenesis are supposedly associated with a host of negative outcomes (e.g., depression, stress, anxiety, memory problems, cognitive impairments, impaired immunity), while high rates are associated with such things as robust health, cognitive advantages, enhanced memory and learning, protection from stress and depression, and high immunity. Many things that we do in life, so the story goes, unknowingly slow down our rate of neurogenesis, but we can increase our rate of neurogenesis through various dietary and lifestyle changes. Basically, we want to reduce, minimize, and eliminate the things that lower our rate of neurogenesis (and diminish brain health), and maximize and do more of those things that increase our rate of neurogenesis (and support brain health).

Some of things that Cortright recommends to support neurogenesis and brain health include the following:

Aerobic exercise Mindfulness meditation Diet (omega 3 fatty acids, blueberries, tumeric, green tea) Good sleep Minimize exposure to neurotoxic environments, stress, etc.

Much of what he’s putting forth with this “neurogenesis” spiel is consistent with my own integral health perspective, and I appreciate how he grounds the many dimensions of holistic health by focusing on how each affects brain health. Many of his recommendations are no-brainers (pardon the pun) from my perspective. Who would argue, for instance, against the health benefits of exercise, good sleep, reduced stress, and a healthy diet?

The specifics about diet can be questioned, however. Having not reviewed “the research,” I’m not prepared to rebut Cortright’s specific recommendations. I can only say that I’ve heard other “experts” contradict many of the specific dietary recommendations he makes, and at this point I’ve almost given up on making sense of all the conflicting information out there on this subject. We all tend to inflate the importance of whatever studies support our pet theories, and to discount or diminish those that present a contradiction. Those of us who are left dizzy by the ever-shifting sands of nutrition science often end up, for lack of a more clear path forward, giving too much weight to our own anecdotal experience. For instance, I have a hard time believing all the “sugar is toxic” hype, in light of the fact that the first two-and-a-half decades of my life were spent eating (and thoroughly enjoying) a ridiculously large amount sugary foods. The quality of my life–in every way and on every level–was very, very high during those young, sugar-fueled years. And yet, I’m supposed to believe I was ingesting high quantities of poison everyday, with no noticeable negative effects?

So, my concern here–again, keeping in mind that I have not waded through all the contradictory research first hand–is that Cortright might be too eager to accept whatever research, perhaps scant and preliminary, that supports his thesis. Neuroscience, in general, seems to be way over-hyped these days, and something about the way Cortright’s book is marketed (e.g., “Unleash your brain’s potential!”) has my internal “hype meter” bouncing around all over the place. But again, I realize that this is a pretty weak criticism, given that I have not read the book. I did, however, watch/listen to these public talks and interviews:

I definitely find Cortright’s ideas on this topic interesting, and I will continue to explore the connections between diet, lifestyle, and brain health. Maybe I’ll even read the guy’s book, so I can comment intelligently on the subject!

NPR gets it wrong about “undiagnosed adult ADHD”

I was scrolling through my twitter feed this morning, enjoying my coffee, when I came across the following headline from NPR Health News: “Can’t Focus? It Might Be Undiagnosed Adult ADHD“. My heart sunk. It seems even the smart folks at NPR are not above peddling the dodgy “mental illness as medical condition” narrative. This shouldn’t surprise me. Just the other day I was tuned in to NPR’s Here and Now, a show I totally dig, and I cringed hard as host Robin Young trotted out the whole “addiction is a disease, just like diabetes and cancer” song and dance. I suppose I find it particularly depressing when otherwise smart, sensitive people demonstrate such a profound and consequential failure of critical thinking. And it’s such a touchy subject to discuss. When I say something like “addiction is most definitely not a disease and is nothing like cancer,” people might think I’m saying that addiction itself is not real, or that the suffering addicts experience is not real. As a mental health professional, it is rather inconvenient that my perspective of mental health is at odds with the most prominent points of view. It is simply a fact that vast swaths of people, both in the general public and across mental health professions, buy into the medical model of mental illness, at least to a significant extent. It’s impossible to escape the language of this way of thinking, the talk of “symptoms,” “diagnoses,” and “treatments,” and all the distorted thinking and misplaced actions that follow.

How can I point out, convincingly and with compassion, that it was wrong and potentially harmful for the hero in the NPR story, psychiatrist Dr. David Goodman , to frame his patient’s lack of attentional focus as a medical condition in need of medical treatment? After all, one of the patients (Kathleen) reported that she was completely and positively transformed by Dr. Goodman’s medical treatment, that she can now finally focus her attention, finish projects she’s started, and stop beating herself up for being a stupid or lazy person. It’s a difficult discussion to have, no doubt. But the truth matters. And the truth is that a lack of attentional focus is not caused by a stimulant deficiency, any more than drowsiness is caused by a stimulant deficiency. Yes, stimulants increase focus and alertness in most people. No, a lack of focus and alertness is not a disease or medical condition. Yes, Kathleen, your lack of attentional control might lead to problems, difficulties, and suffering. These problems are real. Your suffering is real. And yes, stimulants may help. But no, you do not “have” a medical condition, a glitch somewhere in your brain, that is being targeted, treated, or cured by the miracles of modern medicine. The truth is, no one, not even Dr. Goodman, knows why you have trouble focusing your attention. Maybe it is partly how you’re “wired.” Maybe your innate attentional tendencies aren’t a great fit in a society that values a laser-like focus of attention over other ways of taking in the world. Maybe your relationship with electronic devices can be tweaked for the better, and that might make a difference. Maybe your diet factors in somehow. Maybe a lot of it has to do with the fact that you are bored as hell with your job. Who knows for sure? Not Dr. Goodman, no matter how impressive he looks in his white jacket with a stethoscope dangling around his neck.

Yes, it may be comforting to externalize your problem as a “treatable disorder.” But you don’t have to choose between “I have the disease of ADHD. It has nothing to do with how I live my life.” and “It’s all my fault. I’m stupid and lazy.” The truth is that psychological problems are complicated. The truth is that ALL behaviors and experiences are rooted in the brain and body, and yet our neurophysiological processes are also constantly being influenced, fashioned, and shaped by what we do in the world, by the actions we take, by the quality of our interpersonal relations and other psychosocial engagements. So go ahead and take the Ritalin, if it helps. But consider the potential side-effects and health impacts first. And don’t buy into to false notion that Ritalin is curing some illness that you have. Buying into that false notion shuts down consideration of all the psychosocial factors that are well worth considering.

The same goes for the vast majority of psychological problems faced by the vast majority of human beings. Are there neurodevelopmental and genetic anomalies that affect some people? Of course! Can the tools of modern medicine be brought to bear on these and other problems? Of course! But if the medical model of understanding mental health problems was effective in addressing the more common concerns of the general population (as it has been with say, vaccinations for various infectious diseases), then we should see a reduction in the severity and rates of mental illnesses as our medical treatments are being increasingly applied. But we don’t see that, and that’s because the vast majority of psychological problems experienced by the vast majority of human beings are not best understood using the conceptual tools of the medical model.

I know a kid, about ten years old, who takes the antipsychotic medication Risperdal to help control his behavioral outbursts. The meds are helping, no doubt about it. Fewer explosive outbursts. Fewer trips to the hospital. Better grades in school. This kid’s problems are real. His suffering is real. His parents’ suffering is real. But this kid doesn’t have a “disease” that is being “treated” by the Risperdal. He’s not suffering from a Risperdal deficiency or from brain damage in some hypothetical neural circuits that Risperdal might be affecting. Perhaps smoking some marijuana every day would help control his outbursts as well, but that would say nothing about the “cause” of his problems. The truth is, no one knows why he is the way he is. It’s complicated. But thinking of his problem as a “brain disease,” however comforting that might be to him and/or his parents, is bad thinking, wrong thinking, and potentially dangerous thinking. That thinking pushes his parents to accept the often severe side effects of Risperdal, the unknown effects on the child’s developing brain, and to close the door on exploring the many other interventions (e.g., physical exercise, dietary changes, parental-style adjustments, creative outlets, behavioral modification strategies) that may also help to control the child’s outbursts. And psychosocial interventions have the distinct advantage of being side-effect-free, while also building skills and positive behaviors that can shape both subjective experiences and neurophysiological structure in enduring ways.

So, going back to the NPR story that started me on this rant, I’m happy that Kathleen is able to focus her attention in a way that’s more to her liking. But I’m not happy to see NPR falling into the same traps of poor thinking that have been keeping the broken mental health model in place for decades. Decade after decade we apply the same medical model to the problems of mental illness and addiction, and decade after decade we scratch our heads wondering why everything keeps getting worse and worse.

What are some alternatives, you might ask? There are plenty of them. Check out, well… anything on this website, for starters!

Bruce Levine and the anti-authoritarian mental health movement

I stumbled across a fascinating talk by Bruce Levine, a clinical psychologist who has articulated a convincing anti-authoritarian critique of the mainstream American mental health system. In the presentation (called “The Anti-Authoritarian Movement to Rehumanize Mental Health“), Levine defines authoritarian as “an unquestioning obedience to authority, regardless of the merits of authority,” and he laments the fact that so many of his fellow mental health professionals seem to accept the legitimacy of “establishment psychiatry” despite the last several years of fairly damning media coverage. I too have recently lamented the tendency of my peers, graduate students in mental health counseling, to acquiesce–with very little critical pushback–in the face of whatever prevailing points of view are presented by professors, in textbooks, or through representatives of professional organizations. Levine calls for an anti-authoritarian attitude toward establishment perspectives of mental health, whereby we assess the legitimacy of authority and actively resist any authority that is determined to be illegitimate.

I stumbled across a fascinating talk by Bruce Levine, a clinical psychologist who has articulated a convincing anti-authoritarian critique of the mainstream American mental health system. In the presentation (called “The Anti-Authoritarian Movement to Rehumanize Mental Health“), Levine defines authoritarian as “an unquestioning obedience to authority, regardless of the merits of authority,” and he laments the fact that so many of his fellow mental health professionals seem to accept the legitimacy of “establishment psychiatry” despite the last several years of fairly damning media coverage. I too have recently lamented the tendency of my peers, graduate students in mental health counseling, to acquiesce–with very little critical pushback–in the face of whatever prevailing points of view are presented by professors, in textbooks, or through representatives of professional organizations. Levine calls for an anti-authoritarian attitude toward establishment perspectives of mental health, whereby we assess the legitimacy of authority and actively resist any authority that is determined to be illegitimate.

Remember, back in 2007 or 2008, when Senator Chuck Grassley led a congressional inquiry that exposed the undeniable fact that many of the nation’s most influential psychiatrists and “thought leaders” were being scandalously influenced by the pharmaceutical industry? Well, it was all over the mainstream media. We also learned how Dr. Joseph Biederman, the main psychiatric “thought leader” responsible for the 40-fold increase in kids being diagnosed with bipolar disorder, was exposed as a shill for Big Pharma. Then we saw top establishment psychiatrists–from Allen Frances to Thomas Insel–take a subversive turn by either distancing themselves from or flat-out rejecting the validity of the DSM-5.

Levine, in this presentation and in his writing, also reminds us that the effectiveness of some commonly used psychiatric drugs has been seriously called into question by researchers, and that the “biochemical brain imbalance theory” of mental illness has been effectively and repeatedly debunked by many thoughtful commenters in recent years. And yet so many of us in the field of mental health continue to acquiesce to the dictates of establishment psychiatry, even as we pay lip-service to perspectives based on wellness models and integrative perspectives. Why? Why does establishment psychiatry continue to wield its authority so hegemonically despite the loss of credibility?

Levine answers that “drug company money” is just the tip of the iceberg. He points to a broader, more insidious function of establishment psychiatry, whereby it is used to cover up the adverse, dehumanizing, oppressive, alienating aspects of society. In this view, establishment psychiatry serves to discount, invalidate, and marginalize people who don’t conform or adjust to society, or who rebel against it. For instance, schools can often be oppressive and dehumanizing to children, dampening their inherent curiosity and ebullience. For too many kids, failure to adjust to this situation can result in a psychiatric diagnosis and a central nervous system dulled by drugs. For adults, many jobs pound the humanity out of us through daily routines characterized by dullness and disconnection, and too many of us adapt to this state of affairs with a “helping” hand from psychiatry. Psychiatry, according to Levine, has become a tool to cover all of this up, a tool that is put to use in maintaining the status quo. Especially when the general population is fearful, which seems to be the case in our current political and social climate, people are more likely to comply with authority without critical assessment.

And so there you have it, and that’s why it’s important, I think, to support people like Levine who have the guts to “speak truth to power.”

Book review: Impatient Rehab, by J. Larry Vaughan

Just like he did with his previous book, Tell Me How You Feel About That, Larry Vaughan has delivered another powerful, practical, gem of a little book about helping people. More precisely, it’s a book for people who need help, in this case with the problem of addiction.

Just like he did with his previous book, Tell Me How You Feel About That, Larry Vaughan has delivered another powerful, practical, gem of a little book about helping people. More precisely, it’s a book for people who need help, in this case with the problem of addiction.

Although Vaughan warns us up front about his “untrained” writing style, we realize within the first few sentences that this simple, straightforward, utterly-stripped-of-pretense mode of communication is something to be celebrated rather than apologized for. Reading Impatient Rehab feels like a sit-down with a cherished mentor, or an extended, wisdom-filled session with a master therapist. Vaughan speaks plainly and directly to his target audience—i.e., the person in pain who is struggling with a chemical problem. Refreshingly free of the jargon and narrow-mindedness that so often characterizes professional discourse about drug abuse and addiction, Impatient Rehab cuts right through to the human core of this complex issue, and does so with integrity, humor, and a profound respect for the reader.

As a counselor in training, it’s easy for me to imagine having several copies of Impatient Rehab in my future office, and handing them directly to clients who might be suffering from substance use/addiction problems. In fact, that’s exactly what I’m going to do. In the meantime, I recommend this book to any folks—mental health professionals, students in training, medical professionals, friends, family members—who work with or support people struggling with addiction. Most of all, I hope this book finds its way into the hands, heads, and hearts of people who are themselves looking for help to pull through their particular problem and onward toward a life of increased health and happiness.

Shifting Paradigms in Psychiatry: A Dialogue between Dr. Allen Frances & Dr. Lucy Johnstone

The alternative view can be summarized as the belief that people break down for reasons in their lives and relationships—loss, trauma, abuse, poverty, discrimination, domestic violence and so on. These experiences are bound to be reflected in the brain and body in some way, but the evidence suggests that even the most extreme forms of mental distress can be understood in the context of life circumstances and the sense that people have made of them; in other words, by asking not ‘What is wrong with you?’ but ‘What has happened to you?’

Frances, while agreeing with Johnstone that the biomedical model is incomplete and has been oversold–to the detriment of patients–, is concerned that Johnstone’s articulation of an alternative view represents a “psychosocial reductionism” that may prove to be just as incomplete and harmful as the biomedical reductionism it seeks to replace. Frances makes the case for a more balanced approach:

The integrated bio/psycho/social model has a long tradition and remains the best guide to clinical practice. It has always been threatened by reductionisms that would privilege one component over the others–but this interacting tripod of bio/psycho/social approaches is unstable and incomplete without the firm support of all three of its legs. In my view, it is equally mistaken to call for a premature ‘paradigm shift’ tilting toward biology (as was suggested by DSM and NIMH) or a ‘paradigm shift’ tilting toward the psychosocial (as was suggested by the DCP [and Johnstone]). An integrated bio/psycho/social model is essential to understanding each patient and also to unite the mental health professions.

Interesting stuff. I’m just glad to see that this debate is getting some long overdue attention, and I’m hopeful that thoughtful individuals like Johnstone and Frances can make a real difference in pushing the debate (and the field of mental health) forward.

For more see: Does It Make Sense To Scrap Psychiatric Diagnosis?

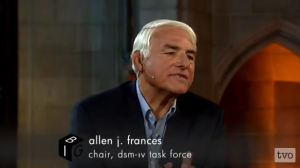

Allen Frances vs. DSM-5

The new version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) is about to drop, and those of us in the mental health field will have to respond and/or adapt to the changes in some way. In my graduate program, the most prevalent response seems to be annoyance at having to learn a new system. Strangely, I’ve heard very little buzz among students and faculty regarding the many critiques of the new manual that have been sprouting up daily across various media outlets over the past year or so. It’s as if students are resigned to accepting whatever dictates come down from the American Psychiatric Association because, well, “that’s the way it is” and “what can we do about it anyway?” I’m not always the most socially engaged student, so perhaps there’s more engaged critical discussion going on than I’m aware of. I hope so.

The new version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) is about to drop, and those of us in the mental health field will have to respond and/or adapt to the changes in some way. In my graduate program, the most prevalent response seems to be annoyance at having to learn a new system. Strangely, I’ve heard very little buzz among students and faculty regarding the many critiques of the new manual that have been sprouting up daily across various media outlets over the past year or so. It’s as if students are resigned to accepting whatever dictates come down from the American Psychiatric Association because, well, “that’s the way it is” and “what can we do about it anyway?” I’m not always the most socially engaged student, so perhaps there’s more engaged critical discussion going on than I’m aware of. I hope so.

Foremost among DSM-5 critics is Allen Frances, the chair of the task force that produced the version of the manual, DSM-IV, that has been in use since 1994. Frances came out of retirement out of a concern that the proposed changes in DSM-5 would lead to a dangerous level of diagnostic inflation, and he’s been blogging, writing articles and books, and giving talks all over the world encouraging people to seriously question the DSM-5’s safety and legitimacy. In a recent opinion piece for New Scientist, Frances summarizes his scathing critique:

In my opinion, the DSM-5 process has been secretive, closed and sloppy – with confidentiality restraints, constantly missed deadlines, botched field testing, the cancellation of an important quality control step, and a rush to publication. A petition for independent scientific review endorsed by 56 mental health organizations was ignored. There is no reason to believe that DSM-5 is safe or scientifically sound.

A more detailed critique (and a mea culpa for the mistakes in DSM-IV) is explored in the following talk, which I find to be very impressive and persuasive:

Psychiatrist and author, Allen J. Frances, believes that mental illnesses are being over-diagnosed. In his lecture, Diagnostic Inflation: Does Everyone Have a Mental Illness?, Dr. Frances outlines why he thinks the DSM-V will lead to millions of people being mislabeled with mental disorders. His lecture was part of Mental Health Matters, an initiative of TVO in association with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Of course, Frances is not alone in criticizing the DSM-5. See my twitter feed for the most credible and thoughtful (in my view) critiques being published on the web.

Integrative trends in counseling education

This semester I’m taking a “Counseling Theory and Practice” course as part of my graduate training. One of my big worries going into the program was that I wouldn’t be able to situate myself within the “mainstream” discourse in the field. When I graduated from college in the early 90s, it seemed as if there weren’t any conventional psychology graduate programs that acknowledged and appreciated an integral or integrative approach to mental health, which was one of the reasons I ended up studying East/West Psychology at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. I thought of myself as being on the cutting edge back in those days, as one of the few who could see through all the reductionistic b.s. of “mainstream” or “conventional” psychology. And there was probably a little bit of truth to that. It’s only been in the last ten years or so that topics once thought of as woo-woo, like mindfulness, have been appreciated and embraced by mental health professionals outside of a few outposts in California, Colorado, and Massachusetts. But today, assuming the textbooks we’re using at New Mexico State University are any indication of wider trends, it seems that a full-on biopsychosocial, integrative approach to counseling theory and practice is at long last having its day. Here’s a quote from Chapter 1 of Gerald Corey’s Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy:

This semester I’m taking a “Counseling Theory and Practice” course as part of my graduate training. One of my big worries going into the program was that I wouldn’t be able to situate myself within the “mainstream” discourse in the field. When I graduated from college in the early 90s, it seemed as if there weren’t any conventional psychology graduate programs that acknowledged and appreciated an integral or integrative approach to mental health, which was one of the reasons I ended up studying East/West Psychology at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. I thought of myself as being on the cutting edge back in those days, as one of the few who could see through all the reductionistic b.s. of “mainstream” or “conventional” psychology. And there was probably a little bit of truth to that. It’s only been in the last ten years or so that topics once thought of as woo-woo, like mindfulness, have been appreciated and embraced by mental health professionals outside of a few outposts in California, Colorado, and Massachusetts. But today, assuming the textbooks we’re using at New Mexico State University are any indication of wider trends, it seems that a full-on biopsychosocial, integrative approach to counseling theory and practice is at long last having its day. Here’s a quote from Chapter 1 of Gerald Corey’s Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy:

To understand human functioning, it is imperative to account for the physical, emotional, mental, social, cultural, political, and spiritual dimensions. If any of these facets of human experience is neglected, a theory is limited in explaining how we think, feel, and act.

Shit, that sounds an awful lot like the blurb on the front page of this website! Could it be that this integral health stuff is no longer such a radical idea?!?! Perhaps I’ll have to let go of this notion that I’m part of the avant-garde! I can live with that, I suppose… :O)

My other textbook, Hackney and Cormier’s The Professional Counselor, has also alluded to an integral-ish perspective right off the bat, within the first few pages:

Each individual is an ecological existence within a cultural context, living with others in an ecological system. One’s intrapersonal dimensions are interdependent with others who share one’s life space.

Sounds a lot like the “woo” I studied in San Francisco back in the day! I can only hope this integrative vibe continues as the semester unfolds. It’ll sure make having to read hundreds of pages per week a lot less painful.